Daniel Grushkin is a science journalist who has written for numerous national publications. He’s a cofounder of GenSpace, New York’s first community lab.

It’s been 25 years since Steven Levy came out with his seminal book Hackers, and we still can’t agree on a definition for them. Hackers are deft programmers and designers, they’re whiz kids who break into computer systems, they’re guys who wear leather overcoats à la The Matrix.

It’s been 25 years since Steven Levy came out with his seminal book Hackers, and we still can’t agree on a definition for them. Hackers are deft programmers and designers, they’re whiz kids who break into computer systems, they’re guys who wear leather overcoats à la The Matrix.

But let’s face it: in popular culture the term “hacking” is cool because it suggests a reversal of power. People who we thought were powerless turn out to be powerful, and those who we thought all-powerful end up weak (or at least silly). It’s cool when a 7-year-old blind boy figures out how to trick phone systems into giving him unlimited free calls by whistling at the right pitch. It’s cool when misfits take down a shady company by exposing their secrets (see Wikileaks or Lisbeth Salander).

It fulfills a fantasy we all have—that through moxie and smarts the little guy can upend the system. (I suspect that if you don’t consider yourself the little guy, then you don’t find it that cool.) But without the little guy on top, it doesn’t come off. Case in point, when China launches a cyber attack on the Pentagon, or when a government agency hacks into the little guy’s computer, it’s not that cool. Actually it’s scary.

I’m not sure who coined the term biohacker, but it sounds super- f#@ing cool. To others it sounds super-f#@ing scary. Unpack the term, and I’ll show you why.

You and I are the little guys in the biohacker scenario, but who’s the big guy? Where’s the reversal? At first you might think, ‘Oh, it’s the corporations and universities that spend billions to do what we’re doing on the cheap.’ I don’t think so. Though we may one day democratize science, if anything, we operate in parallel to these institutions.

I think the phrase biohacking suggests an even bigger “big guy,” at least it does to the popular press and culture-at-large. Hacking, at least in this context, assumes that the system has a purpose. When a hacker hacks a system he subverts its original purpose for his own. The little boy takes a system designed to trade telecommunication for money and makes it free. The misfit takes a system originally meant to secure information and turns it into a system that reveals information.

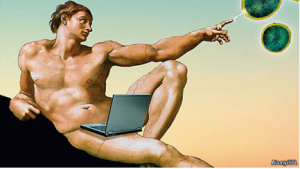

Similarly, for many when you use the term biohack, embedded in the notion is that biology has a purpose, that the designer (presumably God) created it to fulfill that purpose, just like the phone company or the security system. To hack it is to somehow subvert the design, and through it, supplant the designer (again, presumably God). Now granted, if you took an insider’s view of the term “hack” this would all seem preposterous. But look at this graphic from The Economist illustrating the creation of the first synthetic bacteria. That’s man playing the role of God in Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel.

Credit: Economist, May 20th 2010

And you wonder why some of the public sees us as dangerous (parables like the Tower of Babel follow thereafter). At the same time, for others it’s also the reason why “biohacking” seems so cool (in this case, fantasies of creating a more logical world follow thereafter). Because, in a way, it’s the ultimate reversal of power: Hello God, here comes mankind.

Replace the theological with a Darwinian lens and the term again degrades into nonsense. Why? Because “purpose” is a term that doesn’t apply to evolution. A firefly shines bright not because it was designed to, but because it found utility in a string of mutations. Life is a MacGyver, “purpose” only comes after the biological change is made. So if you put the gene to shine bright in another organism (which we do), you are not subverting what some might call “divine will.” You are, however, throwing your own purpose into that life. Whether that organism finds utility in it is up to the organism (and the conditions you set).

Back to the term biohacker: I’m not saying you shouldn’t use it. Go ahead. But when you do, be aware of the associations you’re drumming up. Personally, it’s not worth it because the associations just don’t fit my worldview.

I agree. The term “biohacker” adds a ton of extra thought leadership that is unnecessary with either “citizen scientist” or “amateur biologist”, etc. For example, with biohacker, I find that I need to begin by unpacking the term hacker: convince people that hacking is actually a positive activity and dispel the common notion that biohackers are the biological equivalent of computer hackers that break into your computer and steal your identity and do other nefarious things. My preference is to use words that have less cultural baggage, one that is naturally more positive.

You are obviously not a hacker.

I’m not sure what your point is, but I think the issue is about how self-perception and perceptions of the group by others relate to each other. While self-perception of being a biohacker may be a very, very positive thing. But does forming a group identity around the term biohacker actually put the group itself at disadvantage because of how the general public understands the concept (which is negative)? I think its worth discussion.

Excellent post, I really enjoyed reading it. Especially because of my affinity for word origins and associations.

Even knowing the baggage in biohacking, I still find myself drawn to using it, but it’s certainly true that we need more friendly-yet-cool terms to describe the hobby/career. Although “Citizen Scientist” and “Amateur Biologist”, as Jason suggests, are perfectly factual and useful I find myself uninspired by them. And, while I love DIYbio, the word does not immediately convey what it means, and first impressions are everything.

That need for descriptive coolness may be one reason behind my fondness for describing DIYbio using the term “Garage Biotech”. Garages are cool, and Biotech is cool, so it follows that the combination must surely be additively awesome. This, despite internally distinguishing between DIYbio as the “hobby” and Garage Biotech as the “career” on the continuum of amateur biology.

Thanks, though, for giving such food for thought. Again, great post. 🙂

Yeah, you’re right, the terms “citizen scientist” and “amateur biologist” are quite sterile sounding compared to the additive awesomeness of “garage biotech”.

http://www.pnas.org/content/92/20/9011.full.pdf

This article gives some perspective on the controversy that erupted when recombinant DNA technology was invented in the 70’s. There were people calling for all this research to be banned because they thought scientists would create Frankenbug.